Oct. 14, 2016

By: Michael Feldman

IBM leads initiative to establish coherent memory interface for datacenter gear

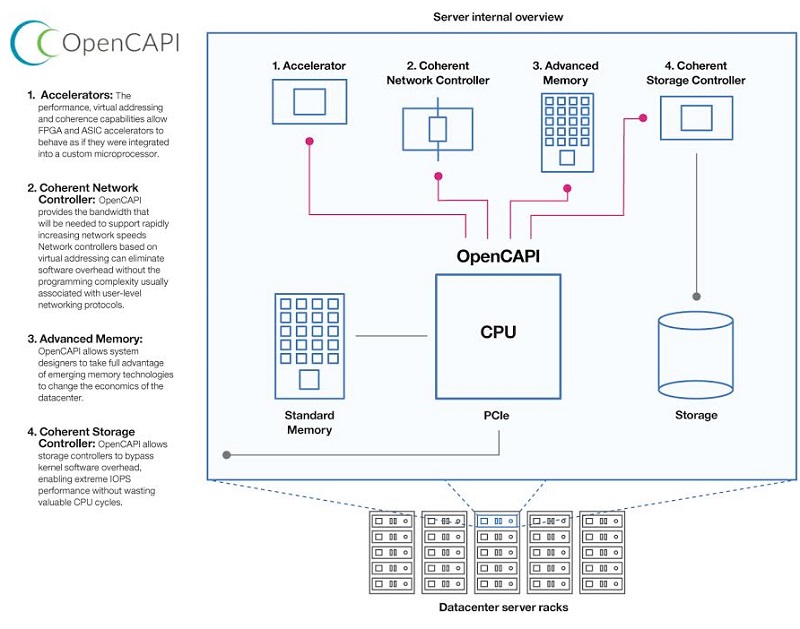

IBM has unveiled OpenCAPI, an open-standard, high-speed bus interface for connecting devices in servers. The announcement coincides with the formation of a consortium of the same name that will manage the new standard, and which initially includes tech heavyweights Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE), Dell EMC, NVIDIA, Mellanox, Micron, Xilinx, and Google. The first OpenCAPI-supported devices and servers are expected to show up in 2017.

Unlike CAPI, IBM’s coherent memory communication protocol that rode on top of PCI Express (PCIe), OpenCAPI is both a new hardware interface and a new protocol, and would obviate the need for PCIe on the motherboard if all the chips were OpenCAPI compliant. The general idea is the same as IBM’s original CAPI: to be able to link together processors, coprocessors network adapters, flash modules, and other devices in the server as equal peers, and which can directly access system memory in the same manner as a CPU.

That’s turns out to be a better model for a variety of attached devices, but especially coprocessors like GPUs and FPGAs and non-volatile memory like flash modules, which would prefer to operate as independently as possible from a central processor. In addition, by separating itself from the PCIe hardware standard, OpenCAPI is also able to offer a much higher bandwidth by virtue of its own physical interface. According to IBM press release, OpenCAPI can deliver 25 gigabits/second per lane, which is about 3 times as fast as PCIe Gen3 and about 1.5 times as fast as PCIe Gen4 (being introduced in 2017). In fact, OpenCAPI speeds look to be on the order of PCIe Gen5, a technology whose final specification and date of availability are currently undefined.

In essence, OpenCAPI offers the performance advantages of something like NVIDIA’s NVlink, but in an industry standard interface like PCIe. The trick, of course, is to get the standard to be widely adopted by vendors so that it can attract a critical mass of hardware and software providers. That often turns out to be a chicken-and-egg problem, but the companies that have initially signed up to the standard represent a decent start: three of the biggest server makers, IBM, HPE, and Dell EMC (the Dell enterprise group under Dell Technologies); processor vendors AMD, NVIDIA, Xilinx, and IBM again; memory device maker Micron; and network device provider Mellanox. “We fully expect the consortium to grow,” said IBM’s Sumit Gupta, who noted that OpenCAPI is being fueled by broader trends in the datacenter toward open standards and heterogeneous platforms.

But at least part of this initiative is meant to blunt the force of Intel, a company that has been busy building a vertical stack of server hardware under its own set of standards. The chipmaker’s dominant grip on server componentry is making customers wary of letting Intel run the table as it gathers more and more server hardware under its dominion. Today that hardware includes a variety of processors (Xeon, Xeon Phi, and FPGAs), its own inter-processor bus (QPI), a network interconnect (Omni-Path), and non-volatile memory devices (3D XPoint and NAND flash SSDs). Some of these components, like Omni-Path, still require a standard PCIe interface for the host adapter, but eventually even this may go away as Intel brings the Omni-Path interface on-chip or on-package, as it has already introduced in the latest Xeon Phi offering.

It wasn’t too long ago that IBM was on this same path of providing vertically integrated solutions using its own proprietary hardware. But times have changed, and today IBM’s interests are better served by a much richer hardware ecosystem than one that can be developed and maintained in-house. In particular, the company’s ambitions in advanced application areas like cognitive computing, analytics, HPC, and the cloud delivery model require a diverse range of components from multiple vendors. Its partnerships with GPU-maker NVIDIA and FPGA-maker Xilinx are indicative of that approach. “What you’re seeing is a trend towards hardware innovation and a renaissance in datacenter architectures based on open standards,” said Gupta.

In the near-term, IBM plans to release OpenCAPI-compliant Power9 processors sometime in the second half of 2017, which will allow the company to build servers based on those chips in that same time frame. The first big test of OpenCAPI might be the Department of Energy’s CORAL supercomputers, Summit and Sierra, which will be powered by such servers and will contain componentry from OpenCAPI vendors IBM, NVIDIA, and Mellanox. At this point though, it’s not clear if NVIDIA and Mellanox will have incorporated the new technology into their GPUs and network adapters, respectively, in the 2017 timeframe. In particular, it is now an open question if and when NVIDIA will replace its proprietary NVLink technology with OpenCAPI.

The specification will be made available to the public through the OpenCAPI consortium website before the end 2016. The spec itself will be free to download for those who have joined the consortium, but can be licensed for those who have not. The consortium will also help prospective vendors with reference designs, technical documentation and access to work groups.